One Anglo-Chinese website explains its use in ‘a situation where someone is not being appreciative of your efforts’, while another uses as an example the notion of sharing something on Facebook that no one ‘likes’. Neither is a satisfactory explanation of the idiom. Like most cheng yu, this one comes with a backstory, but in this case the story does not help to elucidate the meaning. It sounds more contrived than most backstories.

During the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history (771–476 BC), a musician of countrywide renown decided that he would perform a musical recital on his zheng (a stringed instrument that is plucked and strummed like a modern zither) for the benefit of a cow grazing in a nearby field. Even though the musician was thoroughly enraptured by his own playing, the cow was unmoved, apparently preferring to eat the grass in the field rather than respond to the serenade. The story goes on to relate how the musician couldn’t understand the cow’s indifference to his playing.

The ambiguity in this story is obvious: the cow lacked the intellectual capacity necessary to appreciate the music, but the musician must also have been stupid to expect the cow to do anything other than continue eating. The story could be another example of yān ēr dào líng (‘cover ears steal bell’) or kè zhōu qiú jiàn (‘drop sword mark boat’), an example of gross stupidity used to chide someone who has done something unutterably foolish.

However, if, as seems likely, the focus should be on the inability of the cow to appreciate the music, then there are a couple of English aphorisms with roughly the same meaning as duì niú tán qín. The first is a saying attributed to Jesus:

Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you.It is important to remember that Jesus was a Jew, so in this verse he is citing dogs and pigs as ‘unclean’ rather than stupid animals. There is also some evidence (‘trample them under their feet’) that Jesus intended his words to be taken literally, that he was talking about real rather than merely metaphorical jewellery. However, it is in its metaphorical sense that ‘casting pearls before swine’ has become an established phrase in English, in which it is used to describe a situation where someone is too stupid to either appreciate or understand a second person’s ‘pearls of wisdom’.

Matthew 7:6 (Authorized Version)

The second English phrase was used most famously by artist James McNeill Whistler in his libel trial against art critic John Ruskin in 1878. Ruskin had published the following critique of Whistler’s painting Nocturne in Black and Gold — The Falling Rocket:

…Sir Coutts Lindsay [the gallery owner] ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of wilful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.

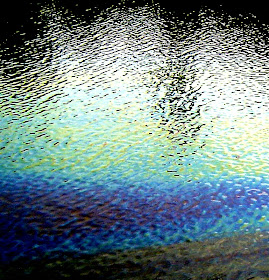

Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold — The Falling Rocket.

It is not surprising that Ruskin was affronted by Whistler’s painting, because he believed that art should have a moral purpose, while Whistler was a proponent of the modernist maxim ‘art for art’s sake’. In other words, this little spat was really about the purpose of art and not the kind of discussion that is often played out in a court of law.

According to contemporary newspaper accounts, Whistler’s testimony during the trial was heavily loaded with sarcasm. This may have played well with the public gallery, but the wily old barrister who represented Ruskin, attorney-general John Holker, clearly knew what he was doing when he asked Whistler a simple question about the success of Nocturne in Black and Gold:

Do you think you could make me see beauty in that picture?If Holker’s intention had been for the witness to appear condescending, his plan worked perfectly. Juries tend to distrust witnesses who appear too clever:

I fear it would be as impossible as for the musician to pour his notes into the ear of a deaf man.A courtroom is no place for light-hearted banter. Whistler may have thought of himself as witty, but insulting a lawyer who asks disarming questions is not a tactic that is likely to impress a jury. And so it proved. Ruskin’s statement is clearly libellous, and the jury’s verdict confirmed this, but when it came to assessing the appropriate level of damages that should be paid, the jury awarded Whistler the smallest possible amount, the derisory sum of one farthing (1/960th of a pound).

Whistler’s retort in the witness box is probably tainted because it has become standard practice to use it in the same condescending manner that Whistler employed, which is where ‘playing piano to a cow’ can perform a useful function. It is unsullied by negative connotations and can be used freely in the type of context in which I heard it: to describe someone who is contemptuous of other people’s ideas because they have absolutely no ideas of their own, someone who is too stupid to understand those ideas. However, if you do choose to use this expression, and most readers will know someone who fits this description, be sure that you are not the cow. It’s an easy mistake to make.